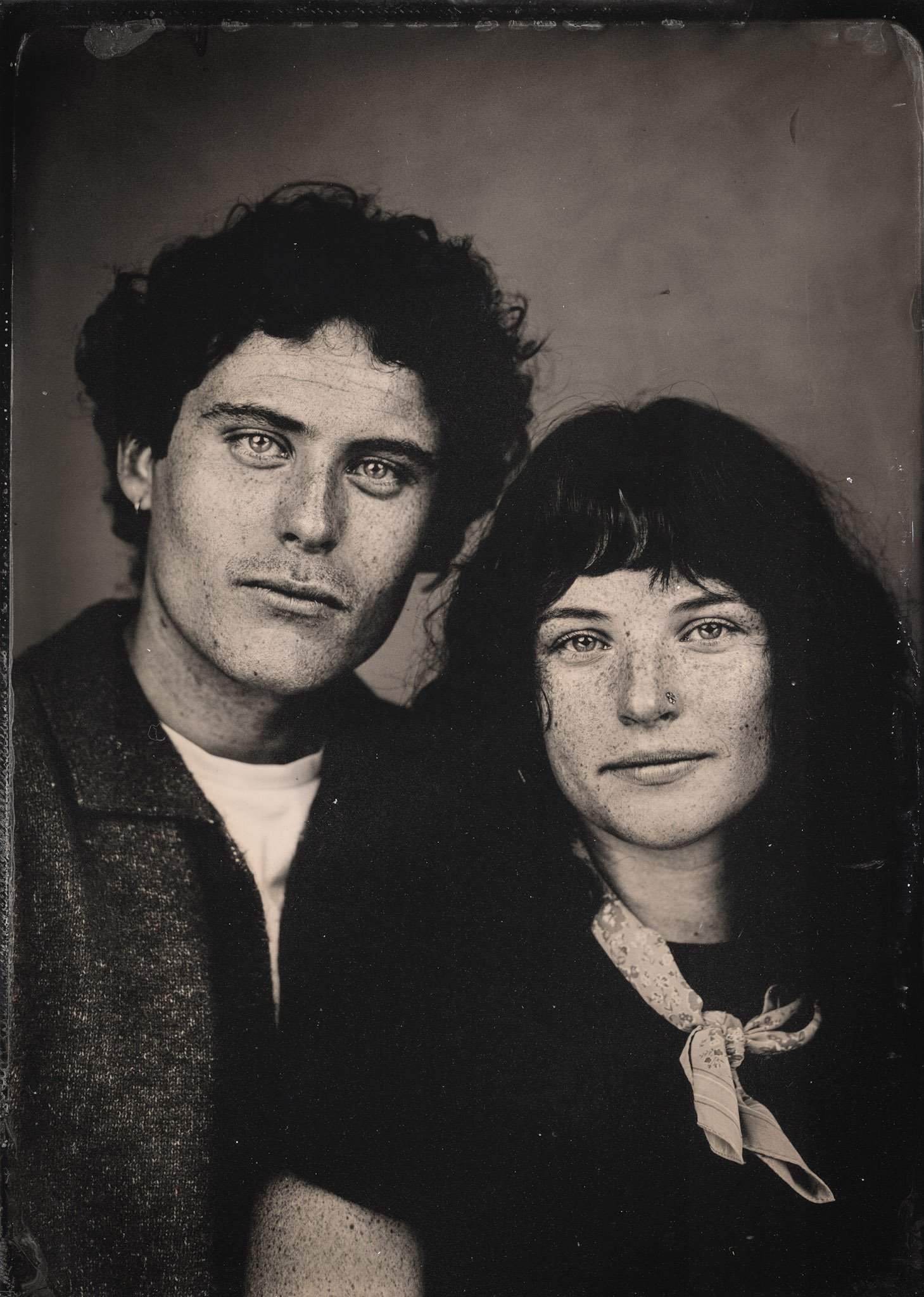

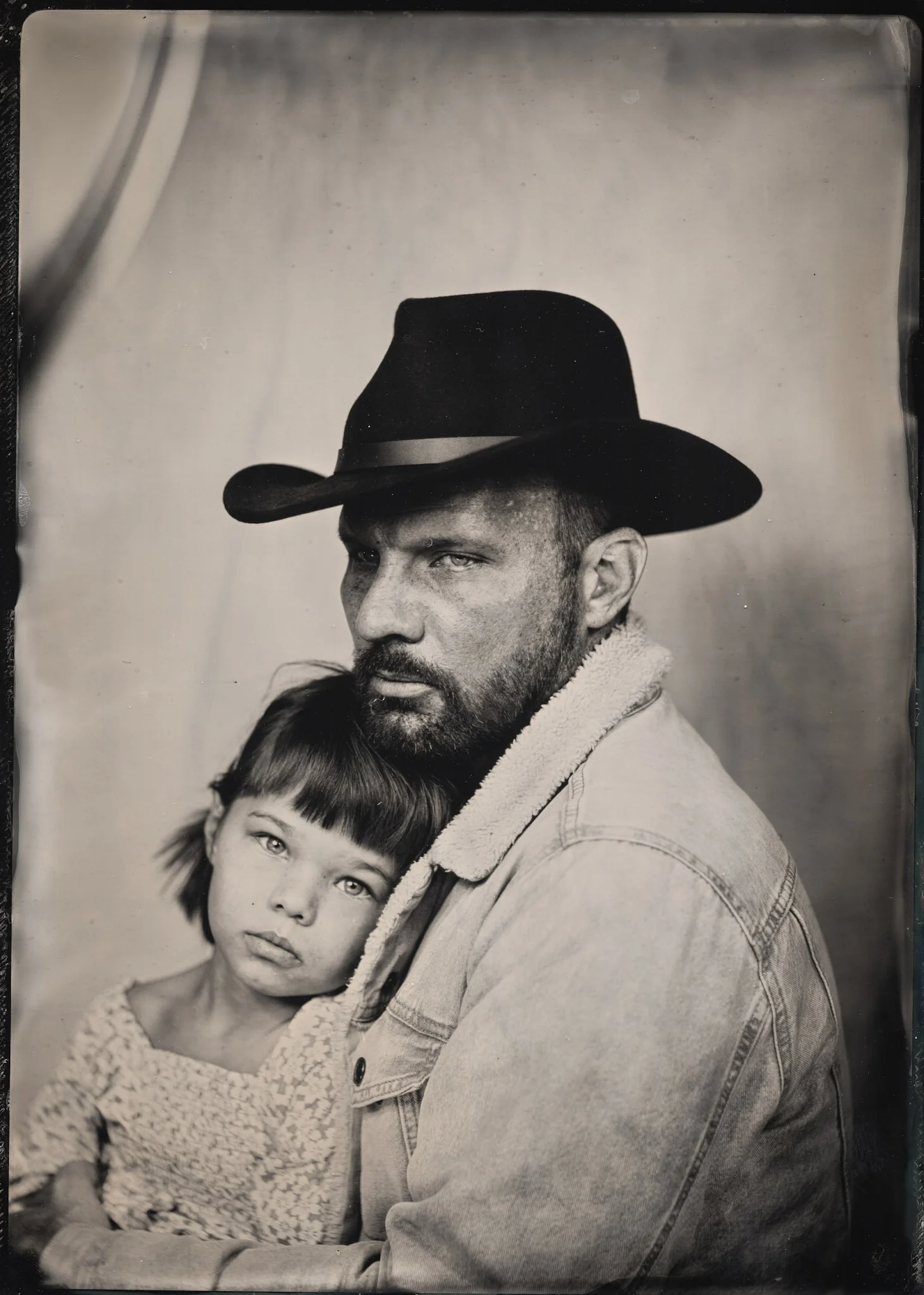

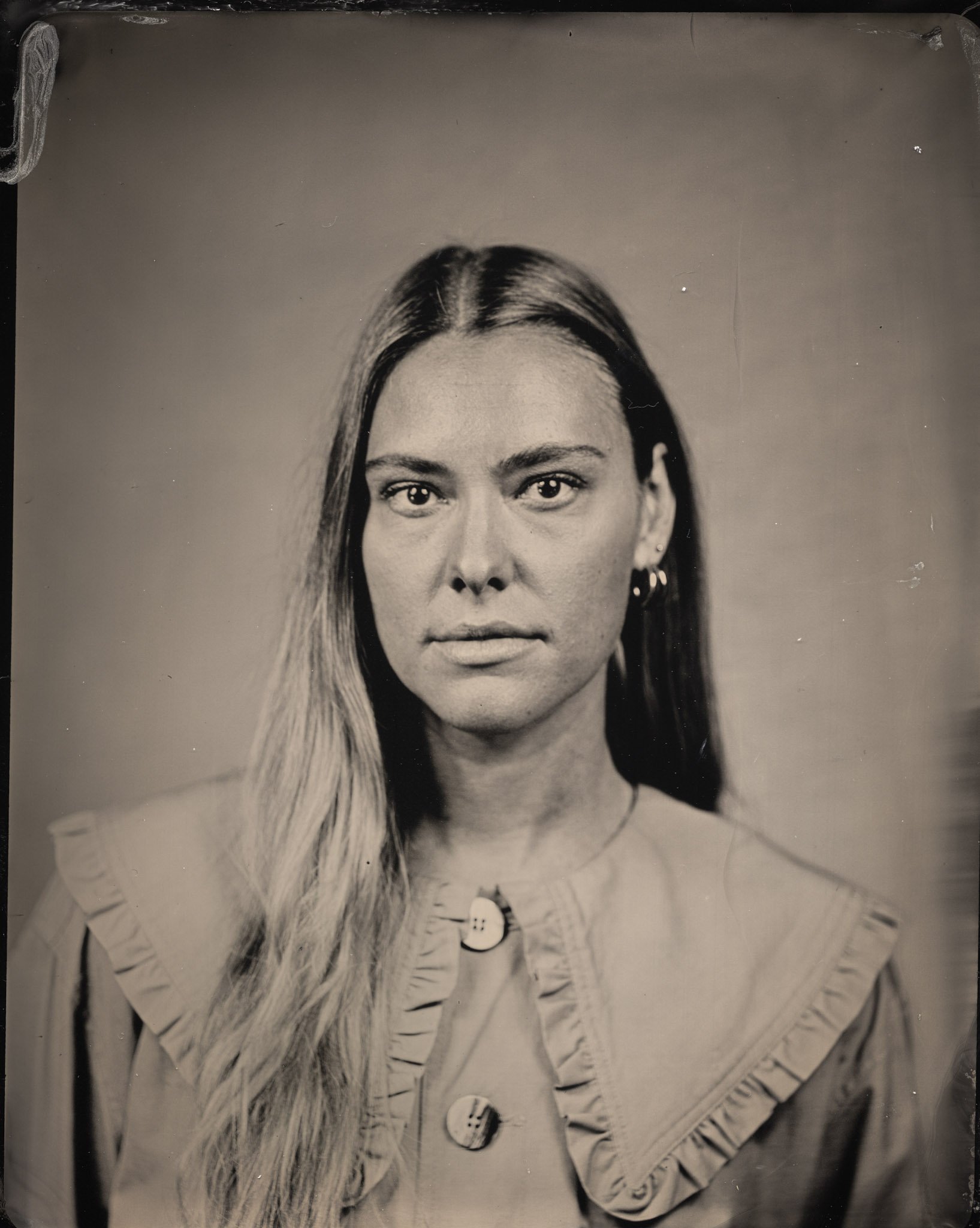

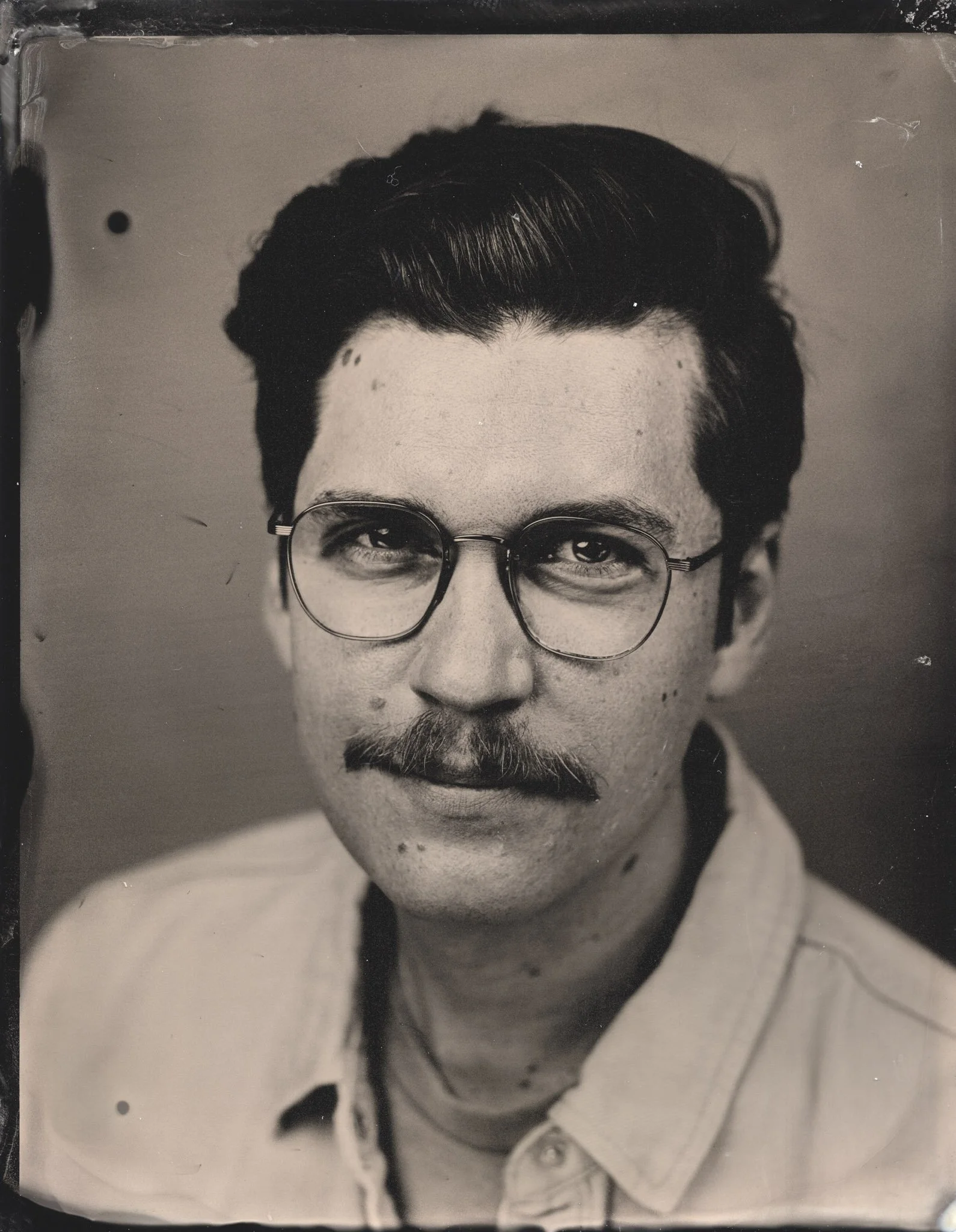

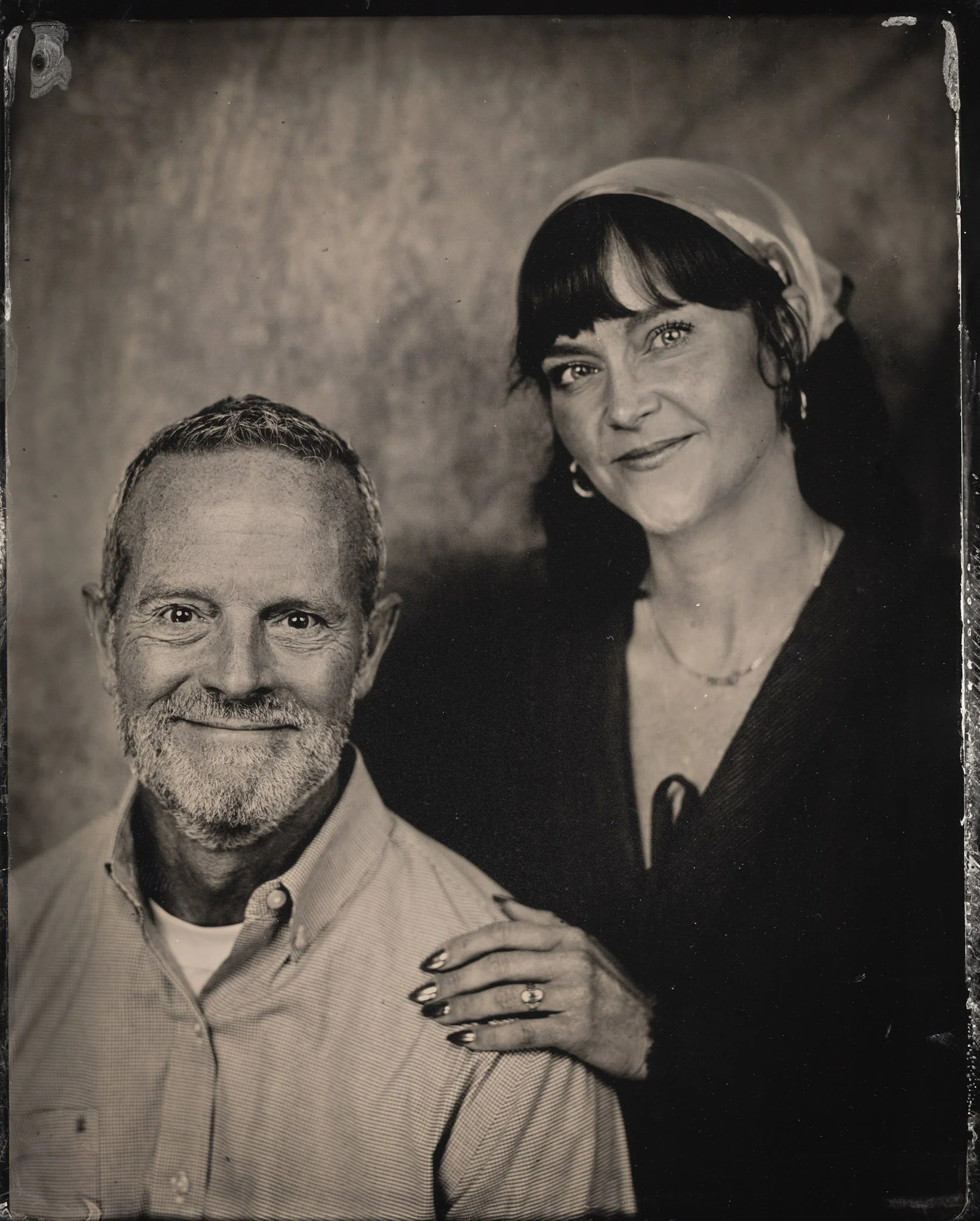

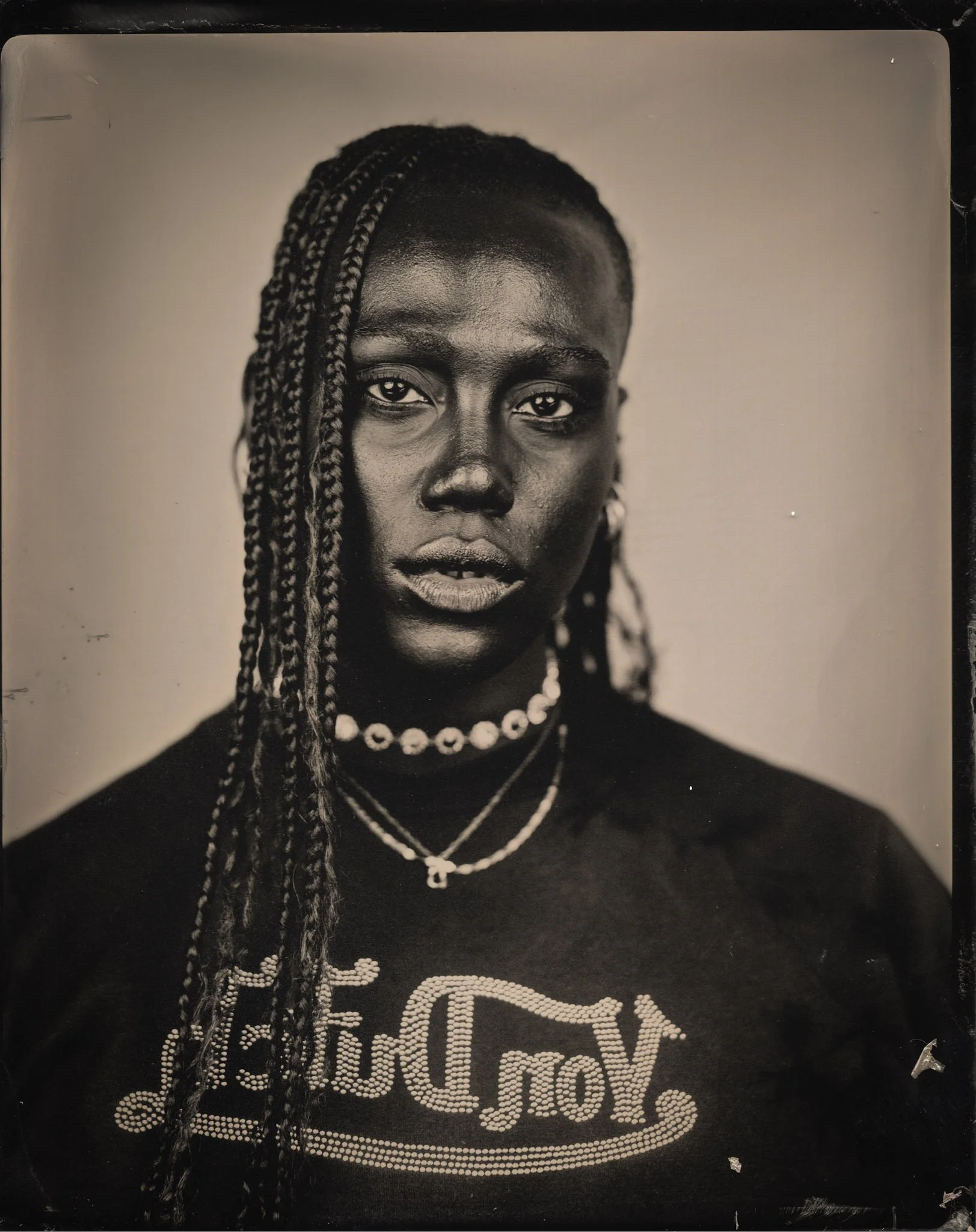

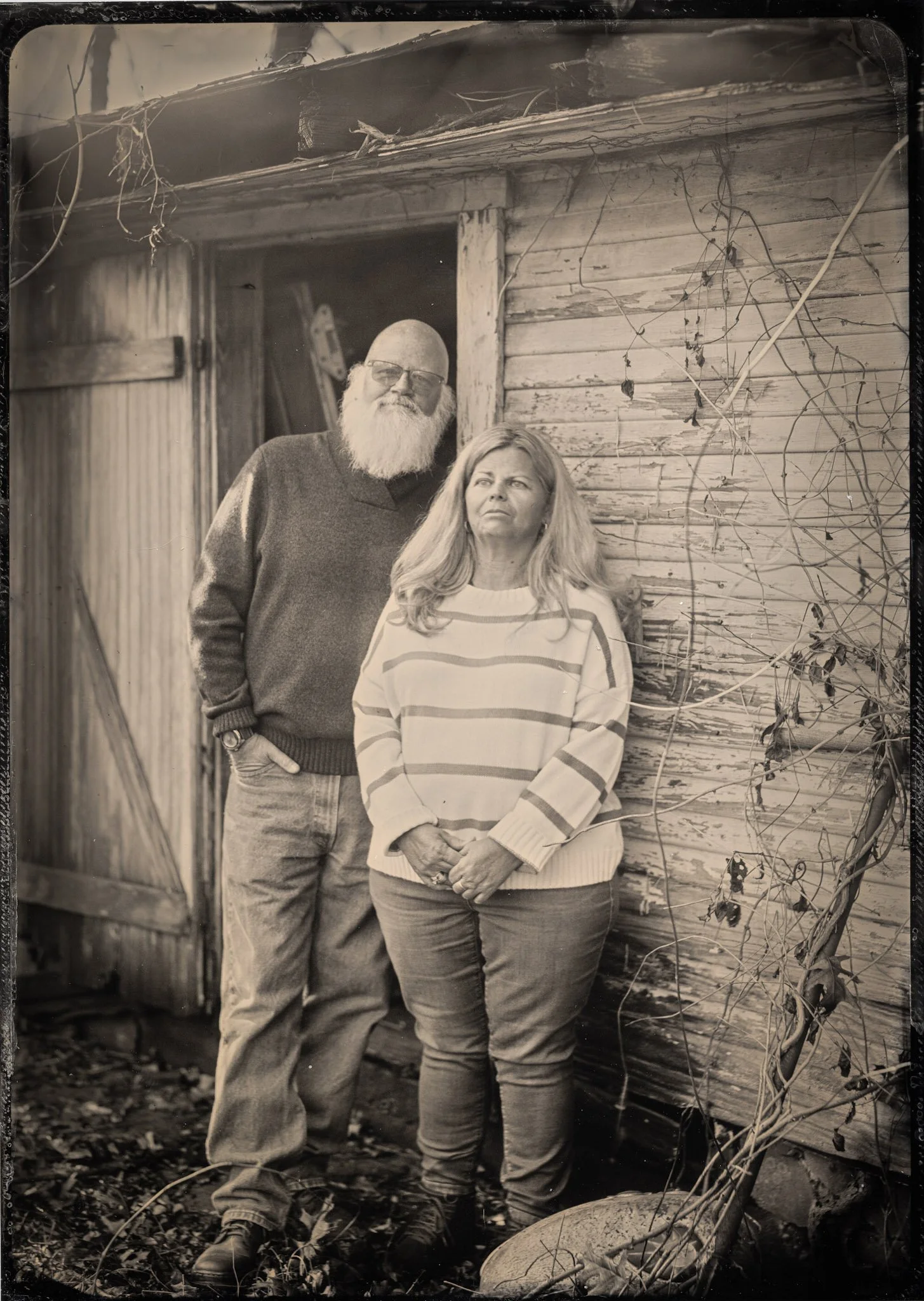

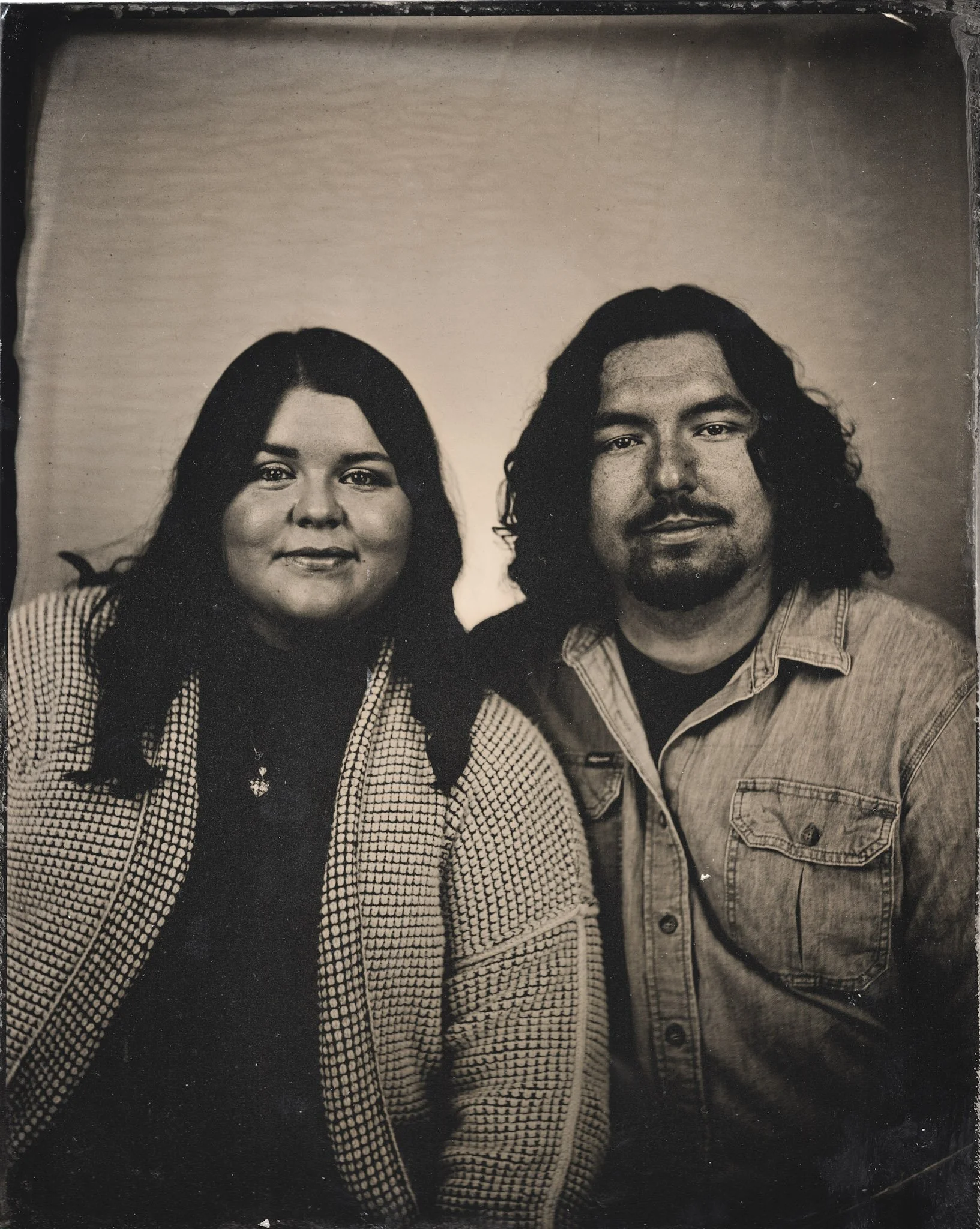

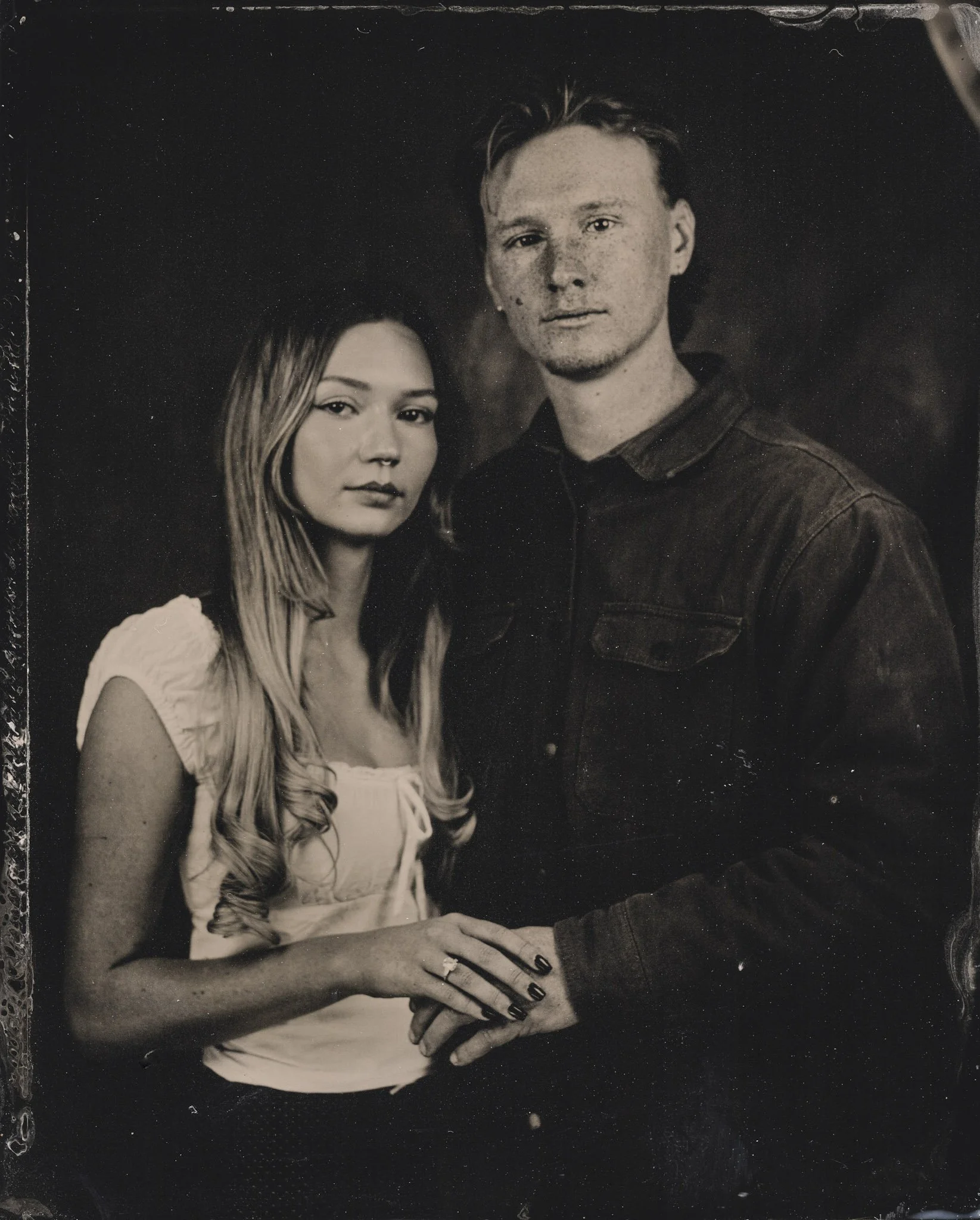

Tintypes

Tintype photography, or the ferrotype

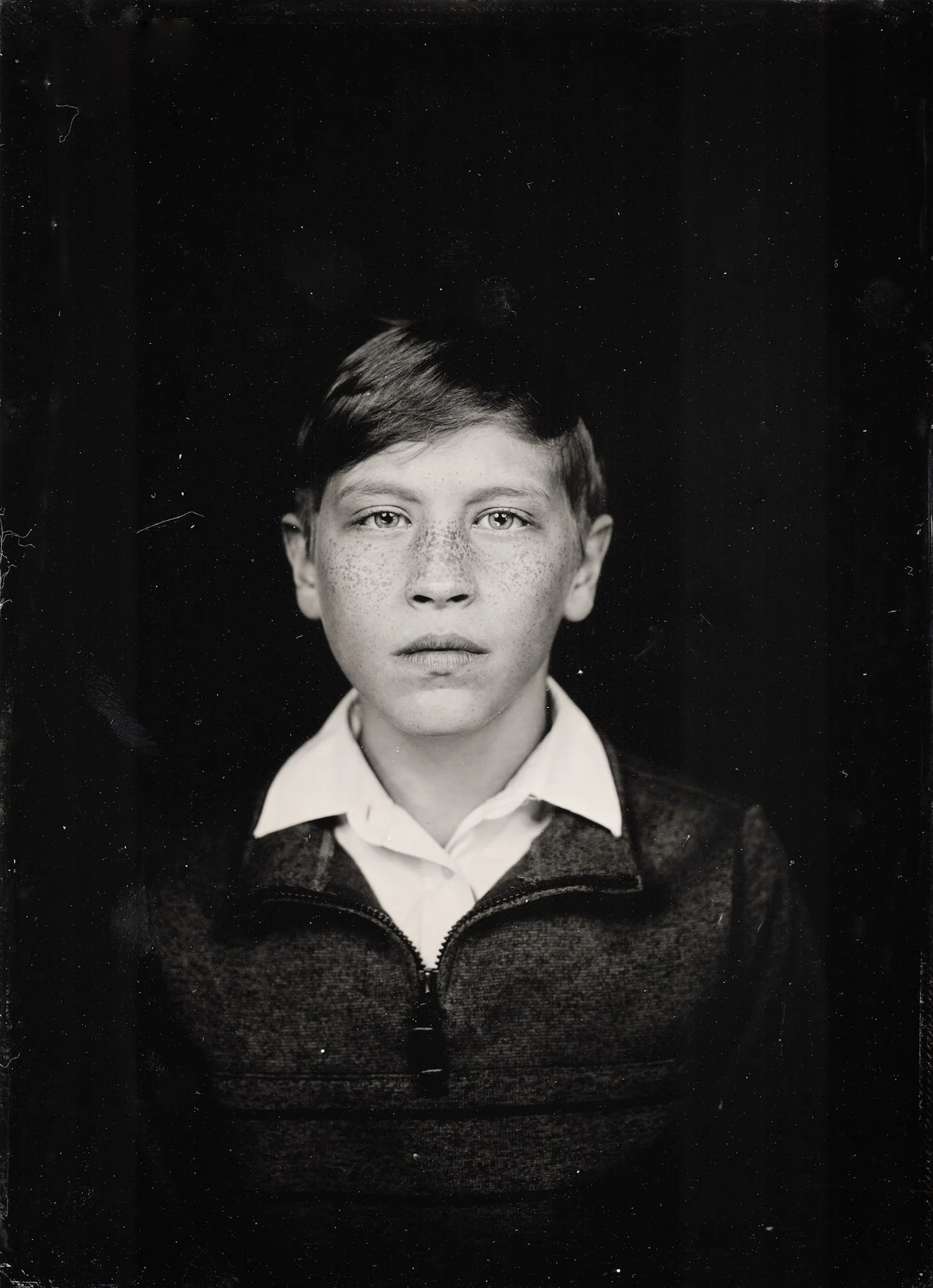

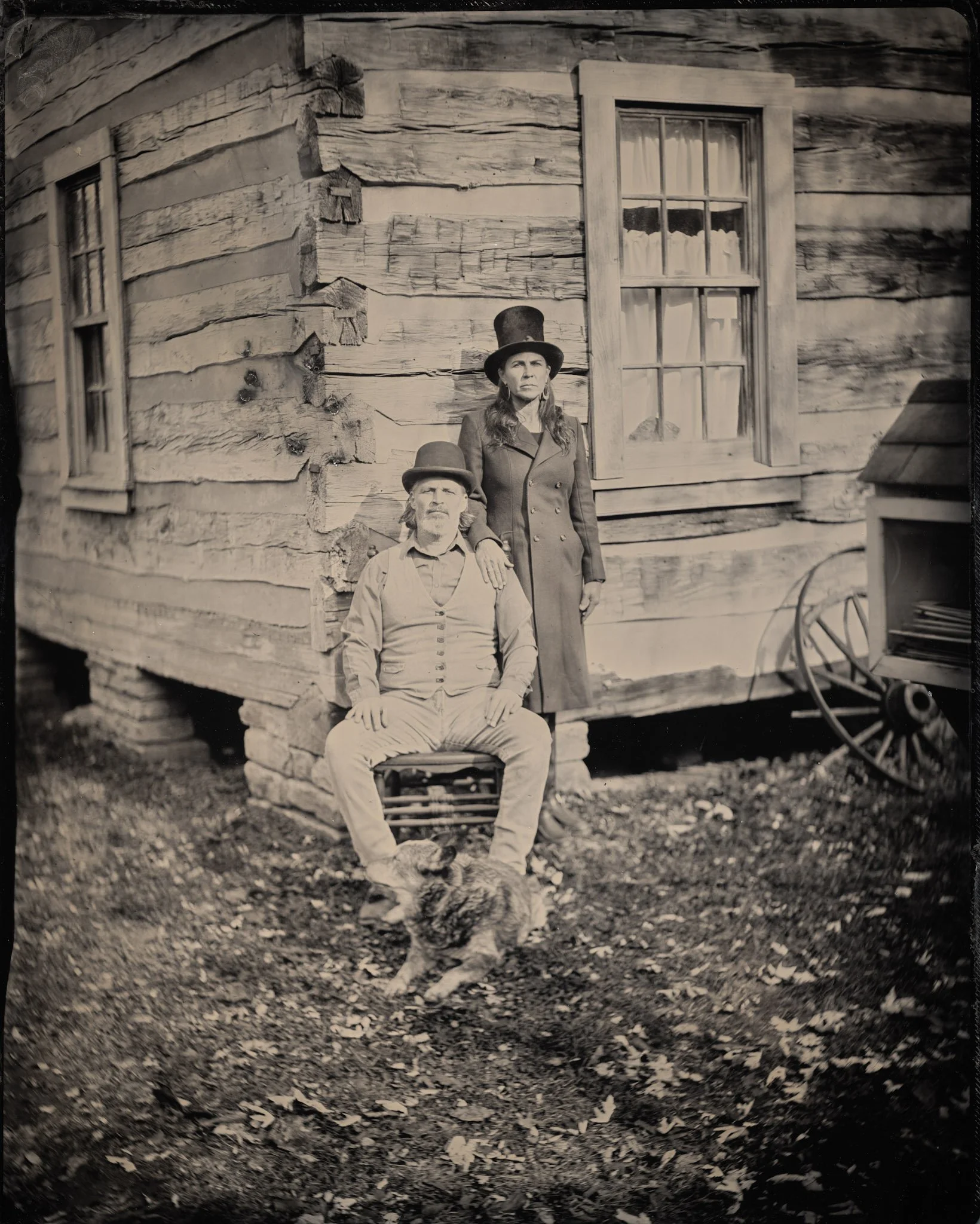

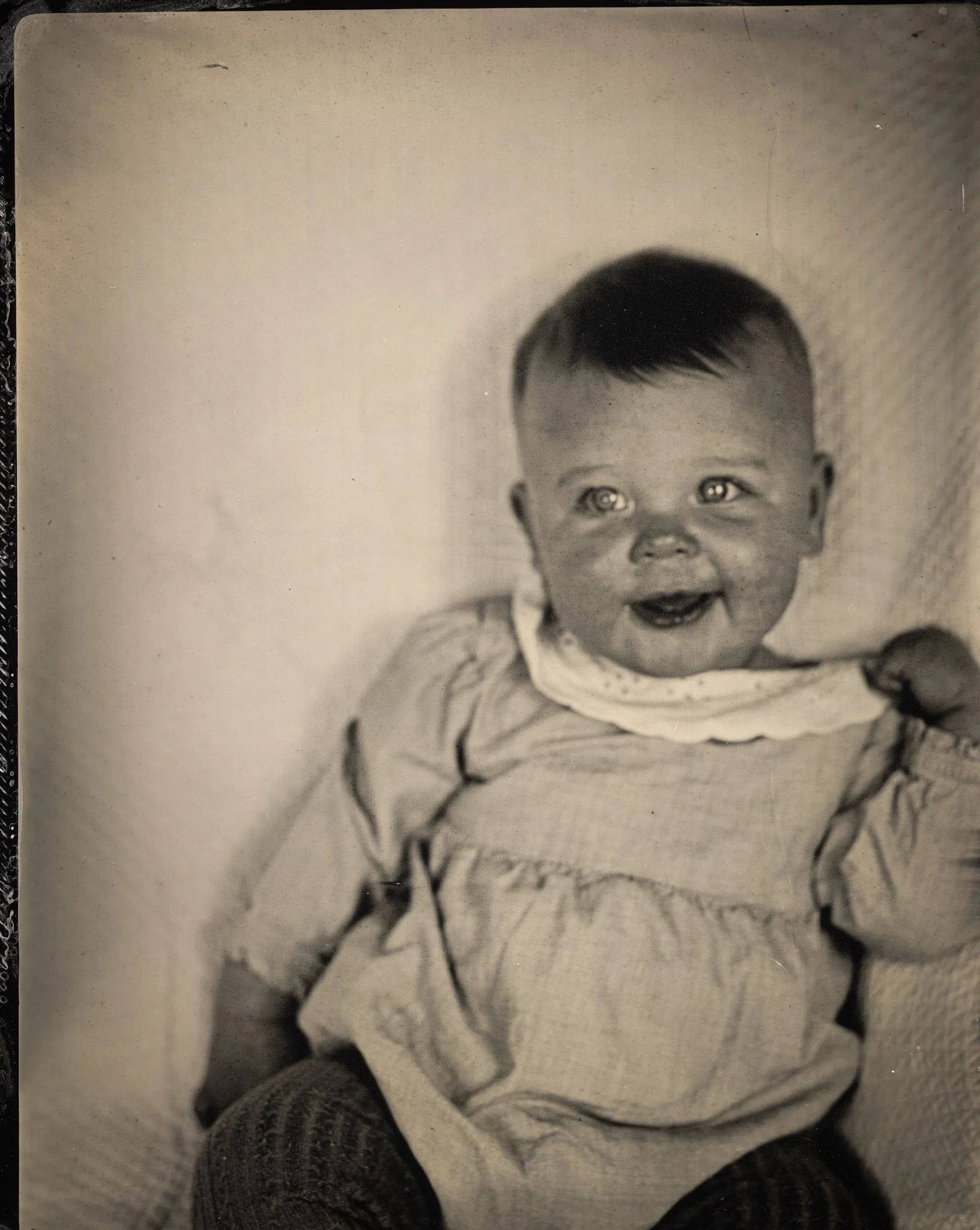

Tintype photography, or the ferrotype, emerged in the mid-19th century as a significant historical innovation that rapidly democratized portraiture. While it is called a tintype, these were never actually done on tin and instead developed on iron (today mostly aluminum). Patented in the US around 1856, this process created a direct positive image on a thin, lacquered sheet of iron, making it exceptionally quick and inexpensive to produce compared to earlier methods like the daguerreotype. This affordability and durability led to its massive popularity, especially during the American Civil War, where soldiers used it to create lasting mementos, establishing the tintype as an essential visual artifact of that era.

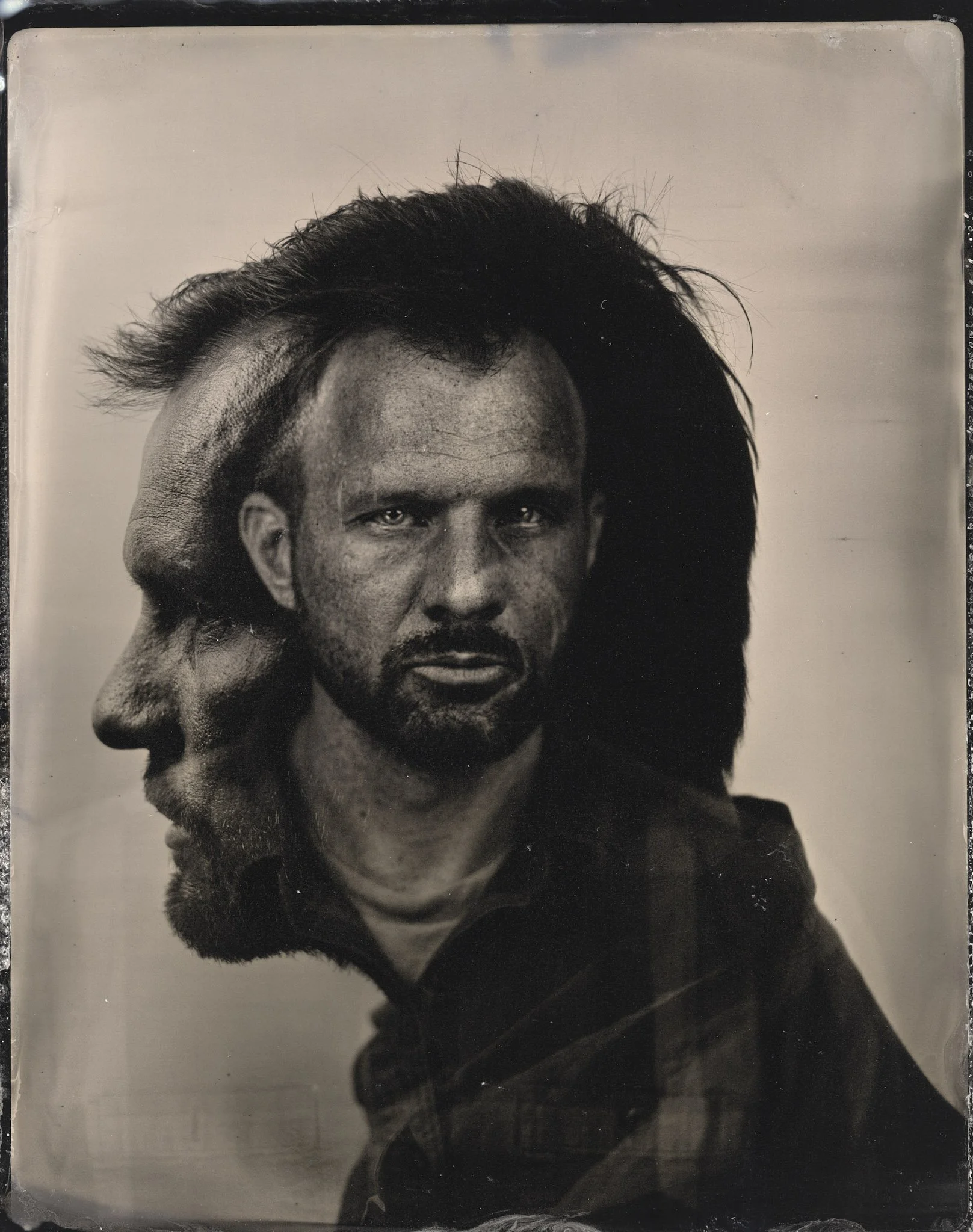

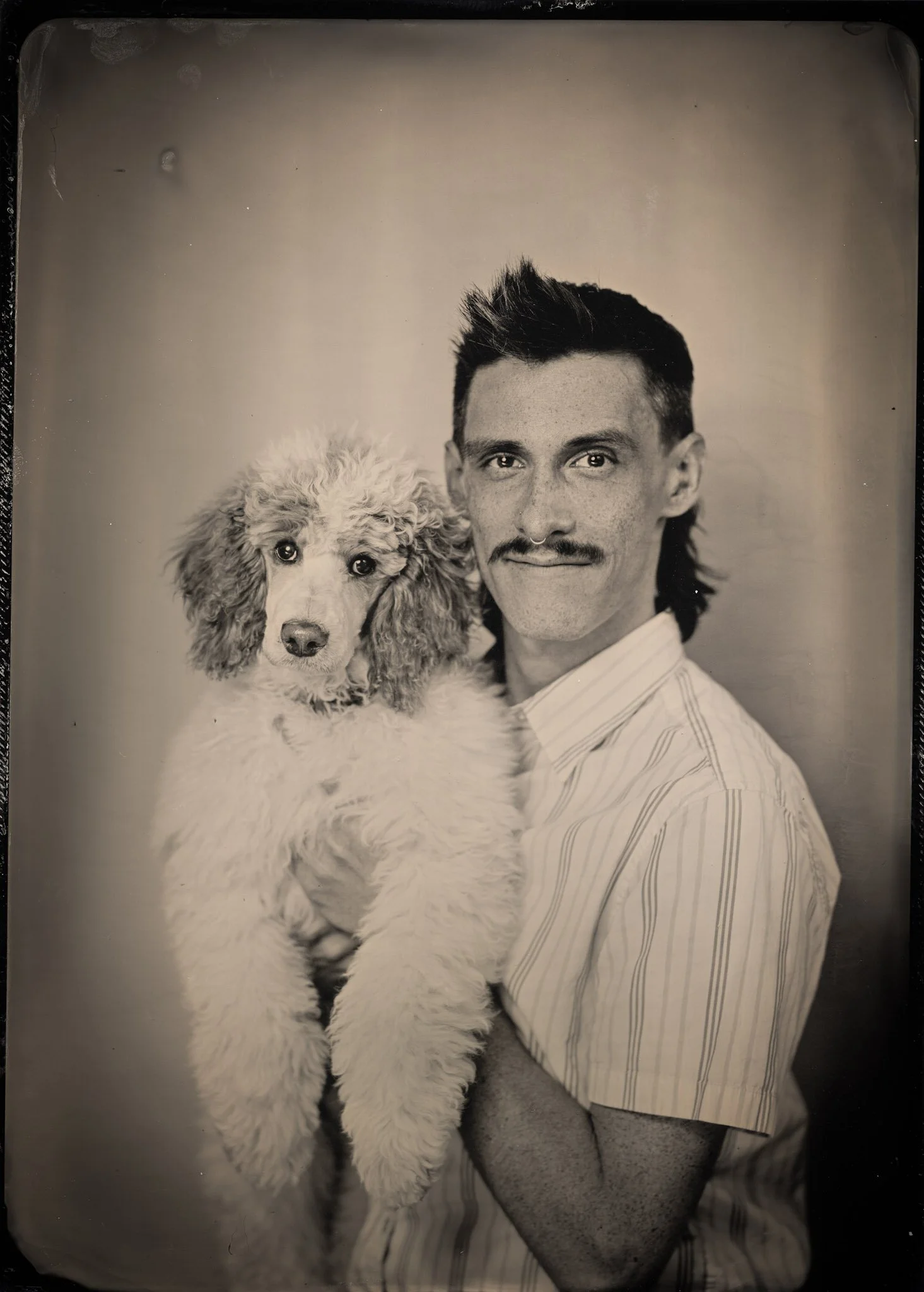

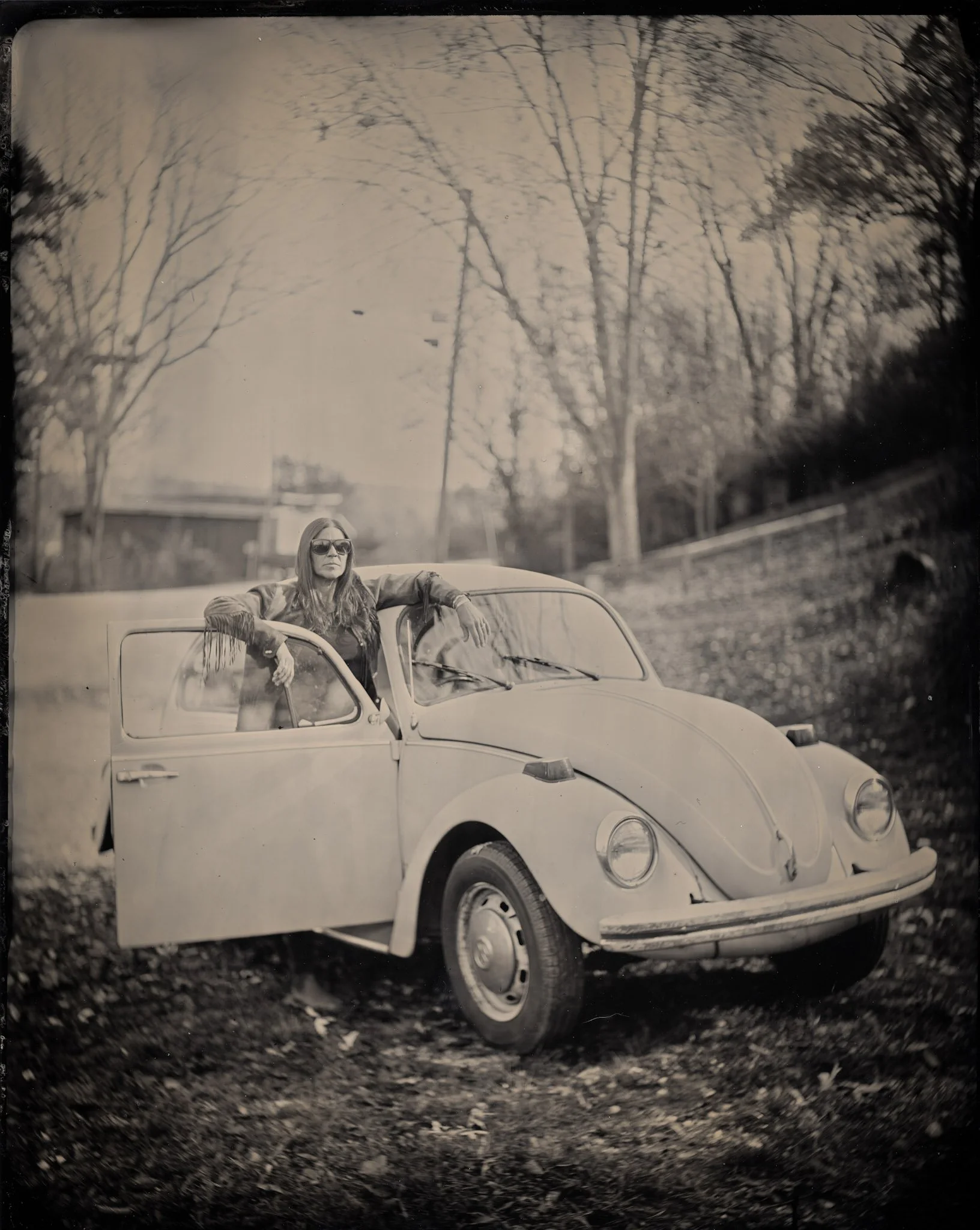

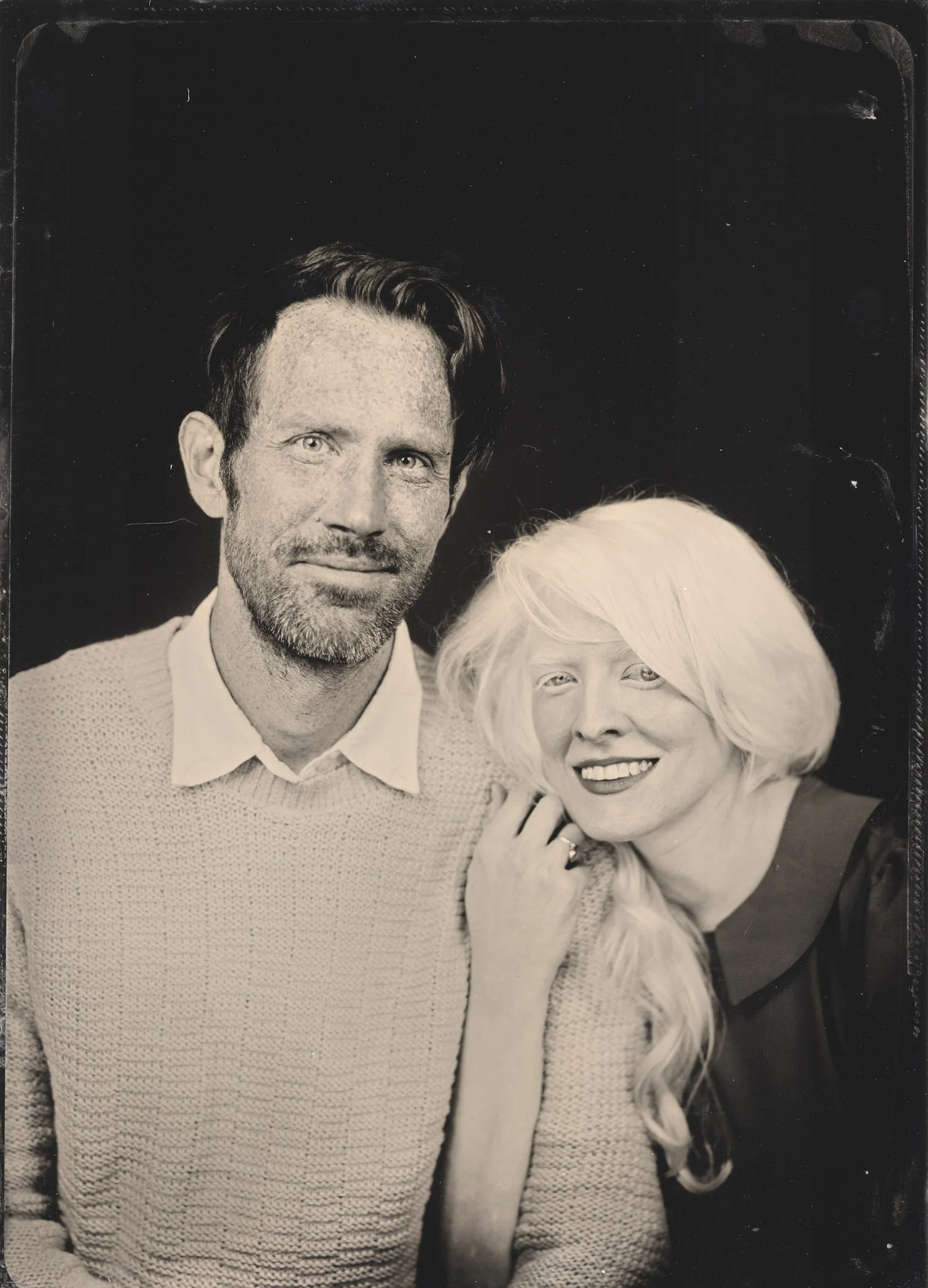

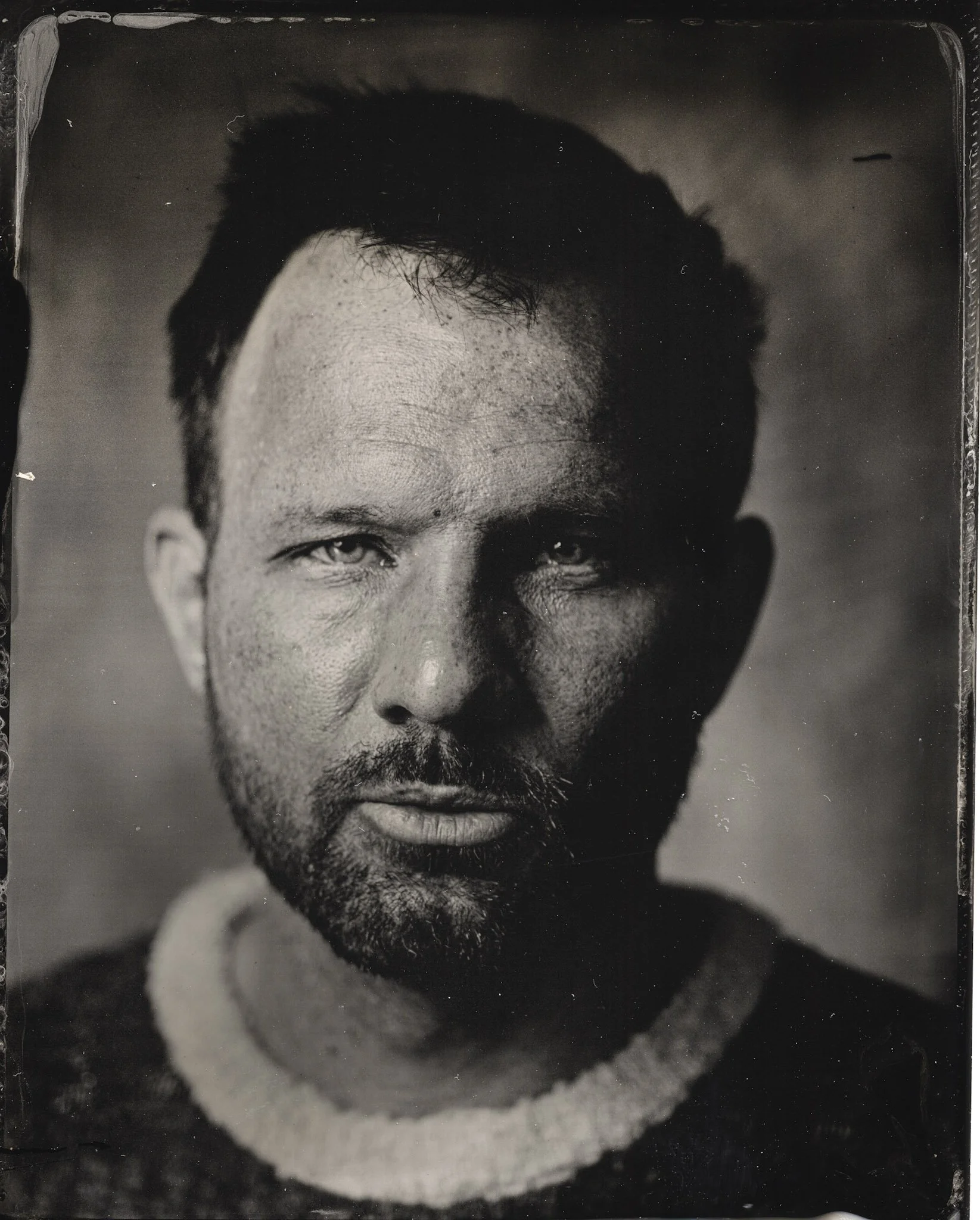

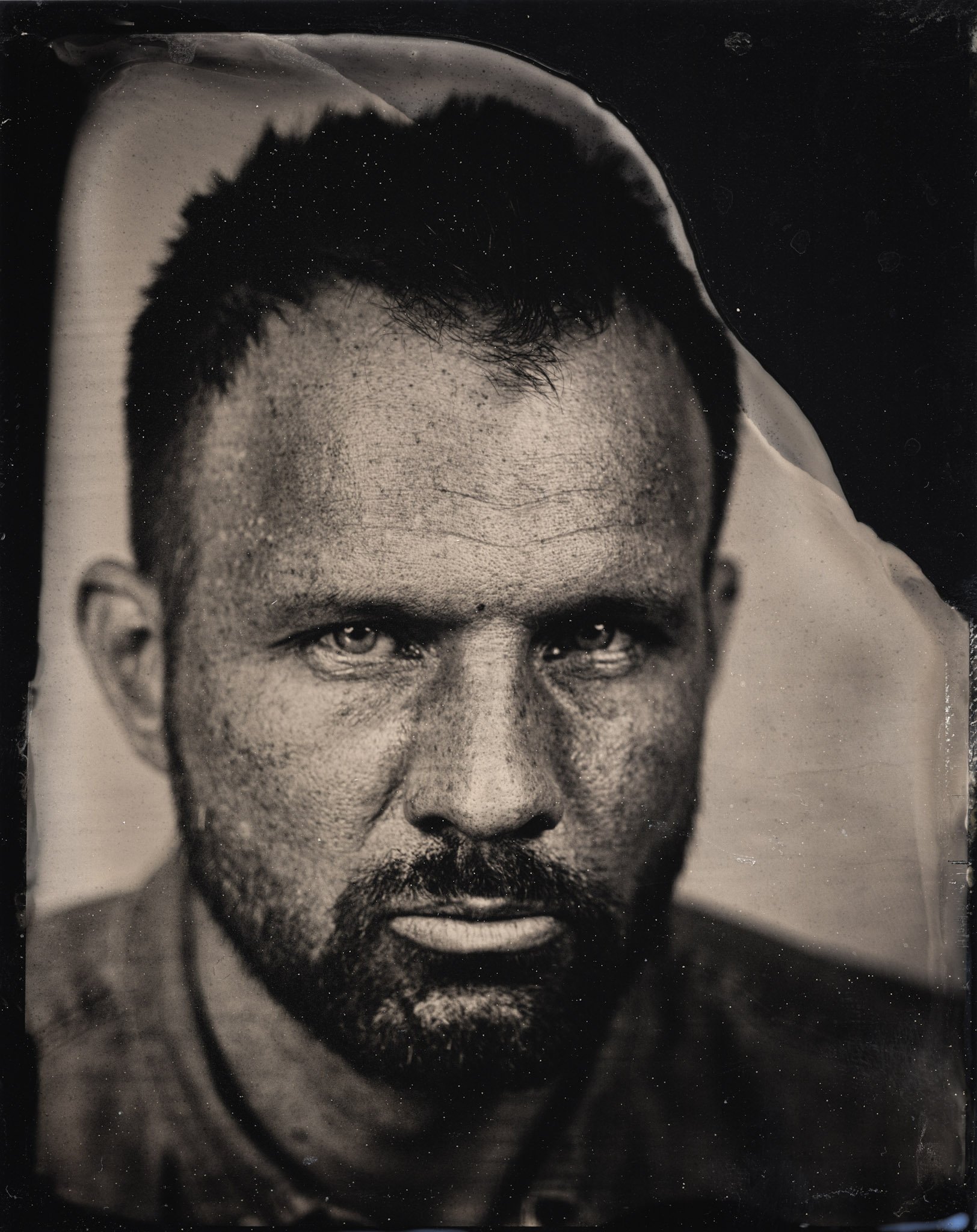

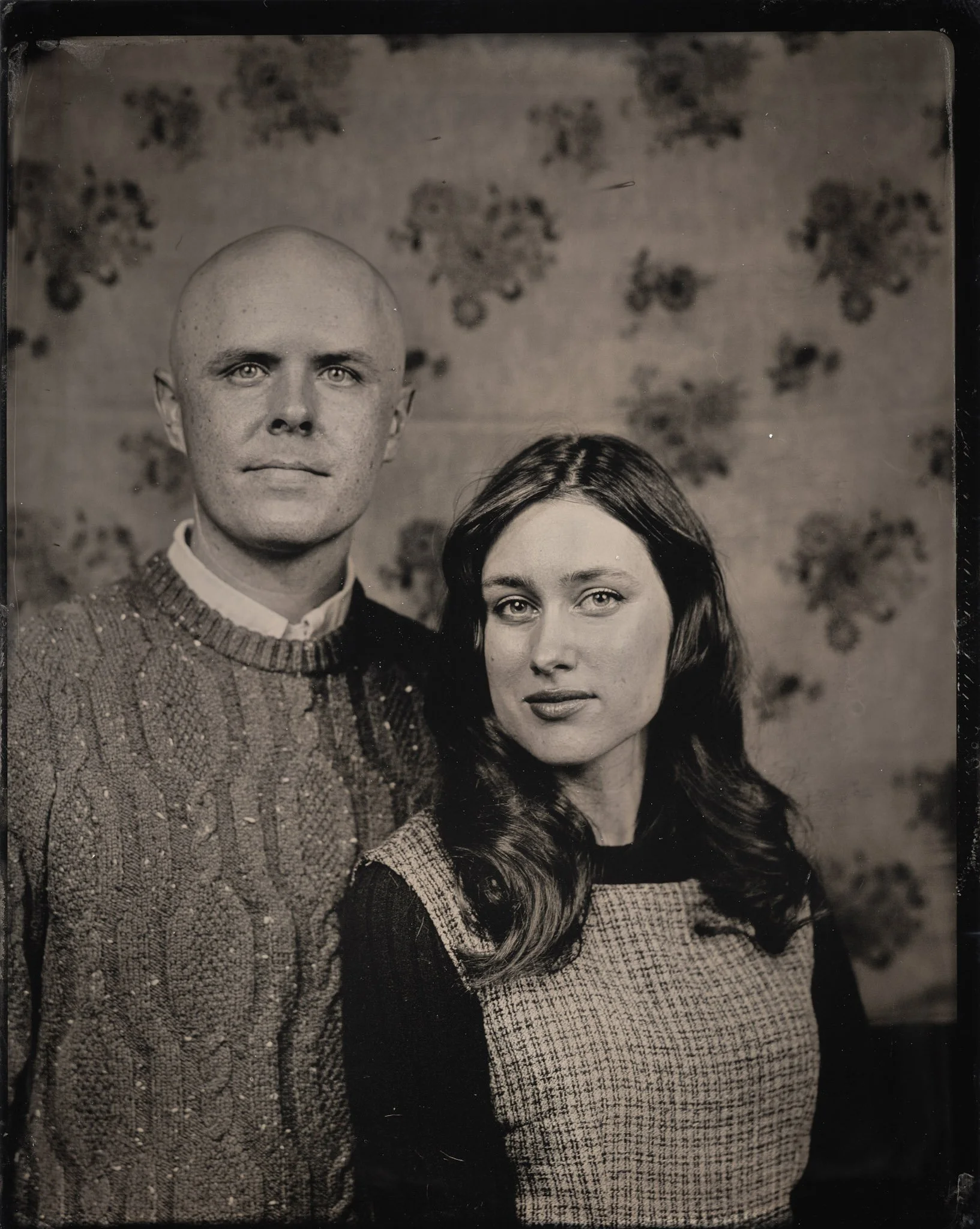

This historical accessibility led to a shift in photographic style. While early studio portraits mimicked the formality of the daguerreotype, the tintype’s rugged and mobile nature allowed photographers to venture out of formal settings, capturing life in less-controlled environments—from the American West to battlefields. This enabled a more candid documentation of everyday people and transient moments. Today, while its necessity has passed, the tintype is having a contemporary artistic revival. Modern practitioners value the hands-on nature of the wet-plate collodion process used to create it, embracing its unique aesthetic—the subtle tonal shifts, the metallic sheen of the iron base, and the inherent physicality of the object—as a deliberate, tactile choice that contrasts sharply with modern digital imagery.